Down and Out in South East Asia by Alex Watts

In the sequel to bestselling food book Down And Out In Padstow And London, failed chef and hack Lennie Nash sets off to eat his way through SE Asia, with a half-baked plan to buy a restaurant.

In the sequel to bestselling food book Down And Out In Padstow And London, failed chef and hack Lennie Nash sets off to eat his way through SE Asia, with a half-baked plan to buy a restaurant.

Along the way, he encounters a host of weird characters from frazzled bar owners to Walter Mitty CIA agents to seedy sexpats to ice zombies four years over on their visa.

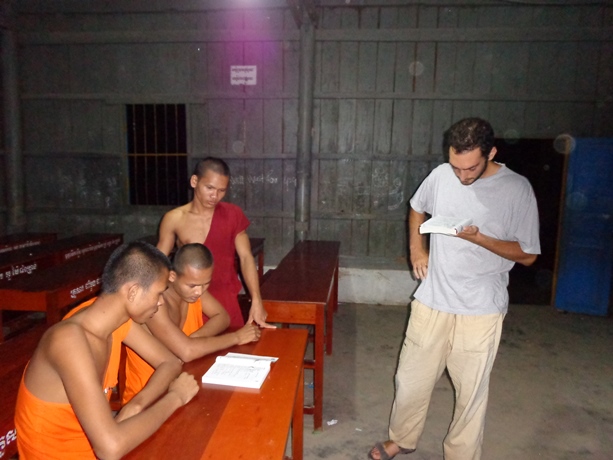

The book is an adventure story, spiked with a heavy dose of backpacker noir, through the eateries, street food stalls, and hazy bars of Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam. In this edited extract, Nash launches a doner kebab business in Sihanoukville with mixed results..

The initial trial of the pop-up restaurant at Rodney’s bar turned out to be an eventful evening. But then, I suppose, what did I expect living so close to Serendipity Beach? It was New Year’s Eve, and the place was dead. Many of the bars and restaurants had shut for the four-day Khmer holiday so the Cambodian cooks, waitresses, and bar girls could go home to their families. Some of them were travelling hundreds of miles to ramshackle farms and slums in northern Cambodia.

Two days on bone-cracking roads, and two days with their loved ones. It was tragic to think that some of the young mothers only saw their children two or three times a year, and then only for a couple of days. The rest of the time the youngsters are brought up by the grandmother while the mother sends money home. I could only wonder at the strength they had to get back on the bus, back to their tiny, shared rooms, knowing they wouldn’t see their children for another few months.

But it wasn’t just the ones with children or parents to support. One bar girl from Battambang had a Cambodian father and Chinese mother who had died in a car crash when she was 11, leaving her to bring up her younger sister and brother.

She’d been employed as a maid in a rich Khmer family’s house, cleaning, cooking, and doing laundry all day for $7 a month and a small room for her siblings to sleep in. Occasionally, “uncles” would wander in at midnight, reeking of rice wine. Tears welled up in her eyes when she told me her story, and she turned away and wiped them.

“I say to Buddha when I pray, next time let me live anywhere, but not this country. Everything is wrong about Cambodia,” she said.

Not that extreme poverty, trafficking, human rights abuses, the global food crisis, and Cambodia’s Great Land Grab were of much concern to Rodney. He kept pointing at all the closed bars and rubbing his hands. By 7pm, he’d snared most of the alcoholics on Victory Hill.

All the food experts were in there, muttering about kebabs, and the best ones they’d had. And whether it was best with naan bread or pita, and whether they liked pickled green chillies in theirs, and one place they’d been to that seared the chillies for a second over the charcoal grill.

Then there were the culinary merits of minced lamb compared with slices, and the divisive issue of whether the chilli sauce should contain grated carrot, and whether it was a gentleman’s right, by God, to insist on “crisp, fresh slices” from the elephant’s foot rather than “stewed slices from the pot”.

“You’ve got the slices, you’ve got the pita, they rip it open, cut it, you’ve got your meat, you’ve got your sauces. Doner kebabs! I fucking love them,” said Rodney.

The boxer was there with his new Cambodian girlfriend. He’d met her in the street two nights ago. He started boasting about how he once lived above a shop “that sold the best fucking lamb doners in the world”. When I told them I only had chicken they shook their heads, and sucked through their teeth like mechanics peering up from a bonnet, and I had to keep explaining about the price of lamb.

WE HAD chipped in $20 each to buy Akara, Rodney’s bar manager, a single mattress and a double one for her parents for the Khmer New Year. They all slept on the floor of their wooden shack down the road. It was heart-breaking to see. I walked past on my way to the beach each day. Her mother and father would always be sat outside playing cards. Akara once muttered: “If my father work, family have mattress.”

We always tipped her well, and Rodney paid her $150 a month in the high season – double the normal wage in Cambodia – and $100 a month in the rainy season. But most of it went to pay off her father’s gambling debts.

“Her father not take care,” Rodney would often say.

With the midday sun burning down, and 35C temperatures in the shade, it was miserable to see a family of six living in that 20ft by 10ft wooden shack without a fan or air con, trying to get to sleep on nailed boards, bugs below them, mosquitoes above them. Akara showered using a bucket filled from a water butt, but came in every day looking immaculate. None of us knew how she did it.

Rodney crept upstairs to get the mattresses and we all gathered round. It was a touching moment. Akara’s face broke into a huge smile and then tears. Her father arrived later on a moped to take the mattresses home. We found out later he drove straight round to the pawn shop with them. I told Rodney I’d give my share of the kebab money to Akara. After that, they all wanted kebabs, and I had eight orders all at once.

It was easy juggling the food, the biggest problem was competing with the beer glasses. There was only one sink, so we battled for space. And talk about an open kitchen. It’s one thing being on show in a restaurant, but at least you’re tucked away behind aquarium glass like a zoo exhibit, or separated by a counter too high to jump over – you don’t have to put up with people walking through the kitchen to get to the toilets.

It was impossible. The food experts were all far too curious, and kept stopping for a chat. At one point, a battle-scarred expat called Gary walked through. He was barred from most of the bars on the Hill, and had been in the country for three years without a visa. There were dark rumours about why he couldn’t go back home.

“What bread are you using for the kebabs, kiddo?” he said, venturing into my side of the kitchen. He was definitely past the water cooler. He was definitely off the toilet right of way I’d marked on the floor with yellow tape. He was definitely on my side of the kitchen.

“Wraps,” I said. I told him I was using wraps.

“Fucking wraps! Jesus! Why don’t you use pita bread, that’s a proper kebab that.”

I politely pointed out that it was just a trial and we were checking out suppliers, and it was easier to get fire-breathing midgets in Sihanoukville than pita bread, and tried to get rid of him. He was still hanging round as I wrapped the kebabs. I was annoyed with Rodney for letting him in the bar in the first place, let alone allowing him to loiter in the kitchen. But then it was my kitchen now. Rodney had told me himself.

“That bit’s mine, this bit’s yours. Lovely jubbly,” he’d said.

I hate people hanging around in the kitchen, but this was a frightening looking man with a teardrop tattoo under one eye, meaning he’d killed someone or been raped in prison, or both, and my usual hints were lost on him. In the end, I was forced to put my arms up and walk towards him in an uncertain shooing manoeuvre. Luckily it worked and he lurched off.

My T-shirt was soon stuck to my back. It was truly unpleasant. I thought about cooking bare-chested, but I didn’t want to put the customers off. Rodney had mentioned putting a fan in the kitchen. He had one standing idle in the bar. He came through at one point and joked: “I’ve been thinking about it. But I thought, no, I want the customers to smell the food! Then they’ll order more!”

I wanted to teach Akara how to make the kebabs, but she was far too busy. Every time I showed her how to cook the chicken there was a shout from the bar. I didn’t know how long I’d be in Sihanoukville for. There were other places I wanted to see along the coast that might be a good spot for a restaurant, and I wanted to make sure she could take over when I left. Even if she sold four kebabs a night, it would double her daily wage, and she could move out of that shack, and away from her thieving parents.

We sold all the kebabs in three hours. An Aussie called Wozza had three in a row, and the Finnish boys had two each. I cleaned down and went to sit with the others. They kept talking about the food and the Finns raised their thumbs. And then a fight broke out between Gary and the boxer’s girlfriend. It turned very ugly, and people began to leave. I tried to calm it at one point, but Gary immediately eyeballed me.

“Believe me Tiger, you don’t want to get involved,” he growled.

He was right. I didn’t. I went off and sat at the bar.

“You don’t need this when you’re trying to sell food,” Wozza whispered to me as he paid his bill.

In the end, Rodney closed the bar and kicked everyone out. He spent the rest of the night muttering to himself in the mirror about how they were all barred, and how his friends had let him down. He brightened up after a couple of hours.

“Do you know something?” he said. “I love it!”

I went back to my room and lay awake for hours. The night had been a disaster. Even the thought of Akara’s joyful tears was soured by the ugly scenes at the end. There would be no mention of the food on the expat forums and rocket-fuelled parish news grapevine, just the trouble.

Then I tried to make light of it. If it wasn’t Cambodia’s first pop-up night, and it probably was, it was definitely the first one to bar all its customers on the opening night. What is it about kebabs?

Down and Out in South East Asia is available to buy on kindle for only $4.99 via Amazon.

And here’s the Amazon link if you’re in the UK.

“”Her father not take care,” Rodney would often say.”

Funny how native English-speakers talk like that to other NES after they’ve been in SE Asia too long!

I enjoyed that. I initially feared some kind of “Off The Rails Part II” but was quickly disabused. Really good insightful commentary on Khmer society for outsiders who aren’t familiar with life here.

Sounds like the former Reggae bar, how is Dellboy doing these days, still alive?

Boo hoo ! How about directing some of that sap towards the goverment that’s causing this distress instead of patronizing them with your tourist visa dollars. Why not boycott that country like so many ofhers because of their shady, nefarious practices ? I wonder why ? Hmmmm….. and I thought I was a small wooden puppet.